Any disruption to how the kneecap communicates with the thigh bone can lead to knee pain during running, leaping, turning, and kicking activities. This can create a range of issues from minor discomfort to complete removal from sport or performance activities.

The most dramatic type of disruption is called a patellar dislocation where the kneecap comes completely out of usual position and can be found on the outside of the thigh bone.

Sometimes the kneecap can be repositioned on the field with a particular relocation movement, while other cases require an emergency room visit and special medication to relax the knee (and patient). If someone has recurrent dislocations, they can often learn how to position and bend the knee to self-reduce or pop the kneecap back into proper position.

NOTE: A patellar dislocation is not the same as a knee dislocation (where the thigh and shin bones come completely out of joint). A knee dislocation involves tearing multiple ligaments that connect the thigh and shin bones and can also include damage to the popliteal artery behind the knee that supplies blood to the lower leg. A true dislocation needs emergent trauma care to evaluate function of the artery and sufficient blood supply to the lower leg.

The kneecap can also partially come out of joint. This is known as a patellar subluxation. This abnormal motion toward the outside of the knee joint can occur on a recurrent basis and lead to lasting episodes of pain and limited bending/straightening of the knee. Patellar subluxations are more common that patellar dislocations and can range in pain and disability from a more minor inconvenience to absolute limitations and removal from usual activities.

RISK FACTORS FOR PATELLAR INSTABILITY

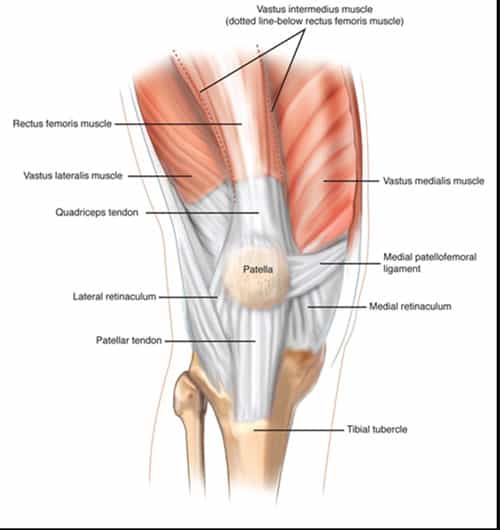

The vastus medialis oblique (VMO), one of the quadricep muscles on the inside of the thigh, is a particular support of the kneecap. The medial patellofemoral ligament and retinacular complex also restricts lateral (outside) motion of the kneecap and can become weaker with either dislocation or subluxation.

Tightness of the iliotibial band (ITB) or the lateral patellar retinaculum on the outside of knee can pull the kneecap outward. An overloaded ITB is often due to weakness of the muscles in the buttock and hip region, which can also cause other stressors at the knee as described below.

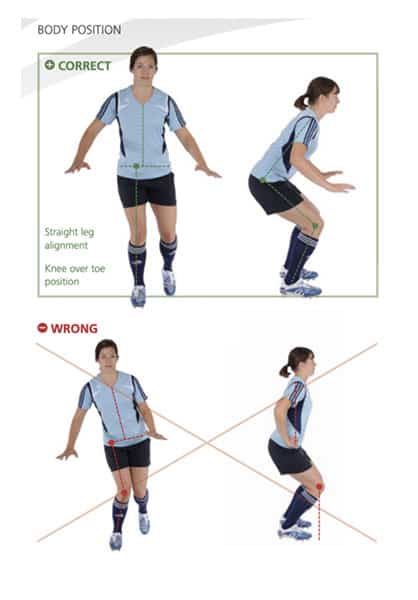

Caving-in of the straight knee (called dynamic valgus on extended knee) with landing from a jump, cutting, or rapidly changing direction can put abnormal stress on all knee structures and especially the kneecap.

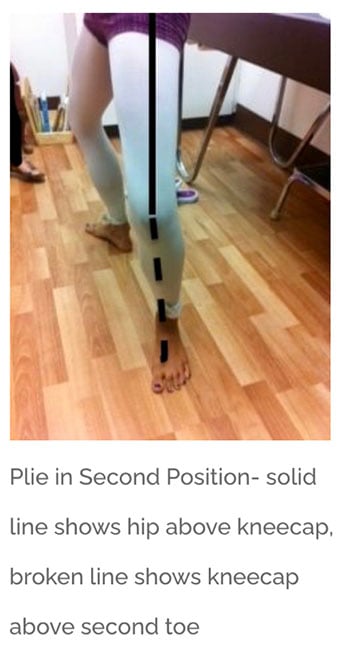

In dancers, I like to evaluate plie technique with turnout in 2nd position. I’ll drop an imaginary line from the kneecap to the floor. If that line falls on top or inside of the big toe, then there is concern about those hip and buttock muscles.

The odds of increased kneecap motion (aka patellar laxity) can be reduced by learning the same landing and cutting skills taught in ACL Injury reduction programs.

RELATED CONTENT ON ACL INJURY REDUCTION: ACL Injury: How a few minutes a week can prevent years of tears

Limitations in motion of the ankle and big toes can also place abnormal rotation on the kneecap and thigh bone. The big toe limitations can particularly a big issue with dancers in the releve or demi-pointe/pointe positions.

RELATED CONTENT: Big Toe Limitations: Don’t Let this Small Joint Cause Big Problems

DEALING WITH PATELLAR INSTABILITY

Speaking of increased motion in other joints, I ask about a history of other joint laxity/dislocations (namely shoulders or fingers) and signs or symptoms of what we call connective tissue disorders. While some increased joint motion can allow athletes and performers to do things that most people can only dream about, excessive connective tissue problems can affect not just joint stability, but also other body regions such as the heart, eyes, and skin.

Imaging studies are commonly ordered in cases of patella instability. X-rays can show bone health (and position of kneecap in thigh bone) while Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) studies are better for evaluating not only bone, but also soft tissue structures on the inside of the knee that can be damaged especially in the case of kneecap dislocations.

Initial treatments for patellar instability can include strengthening exercises for hip, upper leg, and knee regions along with stretching of muscle groups. Knee sleeve braces with padding/support for the outside of the kneecap can help. I’ve learned that some athletes find them too bulky for quick movements while others want to wear one on each knee (so opponents must guess about the injured knee).

There are roles for surgical repair of both patellar dislocations and subluxations. Surgical repair of the support structures on the inside of the knee after a first-time patellar dislocation is a hot topic in sports and dance medicine. Indications include high grade injury to those support structures or damage to the articular cartilage (soft tissue) on the underside of the kneecap or lower thigh bone. In cases of patellar subluxation, prolonged pain and disability may lead to consideration of surgical tightening of structures on the inside of the kneecap or release (loosening) of tissues on the outside of the kneecap.