Are you a dancer who does releve, jumping/leaping, en point or wearing heels?

Do you realize the importance of strong and stable ankles?

Dancing with ankle pain or limitations is no fun and can slow ability to learn new techniques. In extreme cases, too many dancers find out the hard way that repetitive or overly severe ankle sprains lead to career-limiting or ending chronic ankle instability.

Do you have some newfound motivation to protect your ankles?

Good! Let’s jump right into sensible ways to reduce ankle pain and sprains.

Dancers who spend significant time with the foot in a plantarflexed position (heel raised off the ground) put a lot of pressure on support structures around the ankle. Yes, this includes releve, take-of/landing, pointe work and heels. Those support structures include ligaments (that connect bones together) on the inside and outside of the ankle, and multiple muscles on the front, back, inside and outside of the ankle.

An ankle that tends to roll inward or outward when in heel up/toe down is playing with fire for either ligament injury (aka sprains) or overload of bones and muscles.

A dancer’s goal is to keep the ankle in a “neutral” position without too much rolling inward or outward. This neutral position requires contributions from not just the ankle stability but also structures above and below.

FIRST OF ALL, TAKE TIME TO LOOK “HIGHER”

Plie in Second Position – solid line shows hip above kneecap. Broken line shows kneecap above second toe.

Let’s not forget that muscle groups in the hip, pelvis, thigh and knee make big-time contributions to stability of the foot and ankle. A lack of this “central” control, commonly due to injury, fatigue, or pushing a dancer past current level of muscle development, can lead to a higher risk of ankle sprain injuries.

When evaluating any dancer with ankle pain or sprains, I always involve an assessment of hip, pelvis, and knee stability. And if I had to pick one favorite evaluation tool, I’d select looking at plie in second position.

A line that goes over second toe shows most acceptable alignment and hip/upper leg control. If the knee is bent inward (line over or inside of first toe), it can overload the inside of the ankle. If the knee is bent outward (line over or outside of third toe), it can overload the outside of the ankle with an increased risk of sprains.

THEN LOOK LOWER

The big toe can lead to big problems with the ankle.

Some may question why this small joint (aka first metatarsalphalangeal joint or 1st MTP joint) may cause such problems.

Well, let’s review why optimal big toe function is so essential for healthy dance performance.

In many dance positions and movements, including demi-pointe or releve, a dancer ideally should achieve full big toe dorsiflexion.

Limitations in big toe dorsiflexion, known as hallux rigidus, can lead to painful compensations at several joints including the ankle.

When going up on the toes or in a heel raised position, a dancer with limited big toe dorsiflexion will CHEAT by rolling the foot outward and putting the ankle in a rolled inward (inverted position).

Not only is sickling aesthetically unpleasing (instructors aren’t going to be happy), but this position increases ankle sprains and damage to the bones on the outside of the foot. Sickling also can overload the outside of the knee and cause excessive hip internal rotation.

Here’s a simple way to evaluate 1st toe dorsiflexion in a standing position. Examiner lifts the big toes off the floor. In this case, the left toe does not go as high as the right.

Now, you may rightfully ask what causes limited first toe range of motion?

This is a great question with an answer that provides a lead into…

PAYING ATTENTION TO THE INSIDE OF THE ANKLE

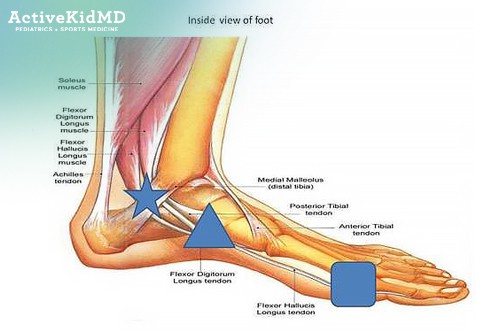

Pain on the inside of the ankle is often due to pinching and limited motion of muscle tendons that are in the tarsal tunnel:

- Flexor Halicus Longus (FHL)

- Posterior Tibialis (PT)

- Flexor Digitorum Communis (FDC)

Tarsal Tunnel at inside of ankle (STAR) Intersection of FHL with neighboring Flexor Digitorum Longus tendon (TRIANGLE) Attachment of FHL to the first bone (proximal phalange) of the big toe (SQUARE)

The FHL goes from the inside of the ankle along the inside of the foot to attach on the underside of first bone of the big toe. Restricted movement of the FHL causes decreased dorsiflexion of the big toe. Stretching of the FHL and friction massage (at STAR AND TRIANGLE above) can increase big toe motion and reduce ankle sprain risk.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE ROLE OF BIG TOE MOTION IN DANCERS

GOING BEHIND THE ANKLE

Moving into pointe or demi-pointe with the ankle in plantarflexion can narrow the space behind the talus (first bone of the foot) and the Achilles tendon. This is where soft tissues can be pinched together – what we medical types call posterior heel impingement. The more time spent in these positions, the higher the chance of irritation.

This pinching may involve the FHL and create the big toe motion limitations.

There’s a chance you’ve been told that an “extra bone” or a ‘bigger bone” may be part of the problem.

Yes, an increased bone prominence can trigger impingement on the back or inside of the ankle that can limit overall range of motion.

CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE ABOUT HEEL PAIN IN DANCERS, THE OS TRIGONUM AND DO I NEED SURGERY?

NOW (FINALLY) CHECK THE OUTSIDE OF THE ANKLE

Even with the best of intentions including good hip/leg strength and solid 1st toe dorsiflexion, lateral (outside) ankle injuries often occur in the dance world.

Stability of the outside of the ankle mostly depends on 4 structures:

- Anterior talofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments

- Peroneous (fibularis) brevis and longus muscles

The ligaments connect bones on the outside of the ligament and are called “passive” restraints since they don’t tighten with movement. Tears to ligaments are called sprains.

The peroneous brevis muscle runs along the outside of the ankle down to the fifth metatarsal bone on the outside of the foot. It is considered an “active” restrain since it can get tighter with movement and limit ankle rolling in. Injuries to muscles (or tendons that attach a muscle to a bone) are called strains.

The peroneous longus goes around the outside of the ankle and crosses under the midfoot to attach to the 1st metacarpal. A properly functioning peroneous longus pulls down the 1st metacarpal head and allows that key increase in big toe dorsiflexion.

Injuries to the outside of the ankle often come from awkward jump landings where the foot rolls inwards. Dancers who are fatigued are at higher risk. Landing on someone else’s foot or a wet spot on the dance floor are also high-risk situations.

Once sprained (torn), ligaments never “fully” heal. They can have scar tissue fill in the gap of tears but will have some aspect of feeling looser than before the injury. Braces and taping may provide some external support. Building strength in the ankle (like the peroneal muscles) and entire leg is a key to protect the injured ligaments.

Here is an essential point – after an ankle sprain, even and most especially with a first-time injury, don’t cut short any aspect of rehabilitation.

The dancer who has no swelling, full motion, and appropriate strength of the entire leg (from hip to toes) is in the best position to return. A dancer who is 85-90% recovered (a point where many try to get back to full activity) is a set-up for future injury. The highest risk for future ankle injury is under-rehabilitation of a past injury.

Strong and stable ankles are essential for dancers. Don’t let ankle pain and sprains derail your dance activities and career!

This blog is designed to provide general advice and is not intended to diagnose or treat any injury as a substitute or replacement for a complete evaluation by your trusted medical professional.

If you need a specialist for any type of dance injury or illness, please contact a sports medicine specialist to schedule a complete medical evaluation.